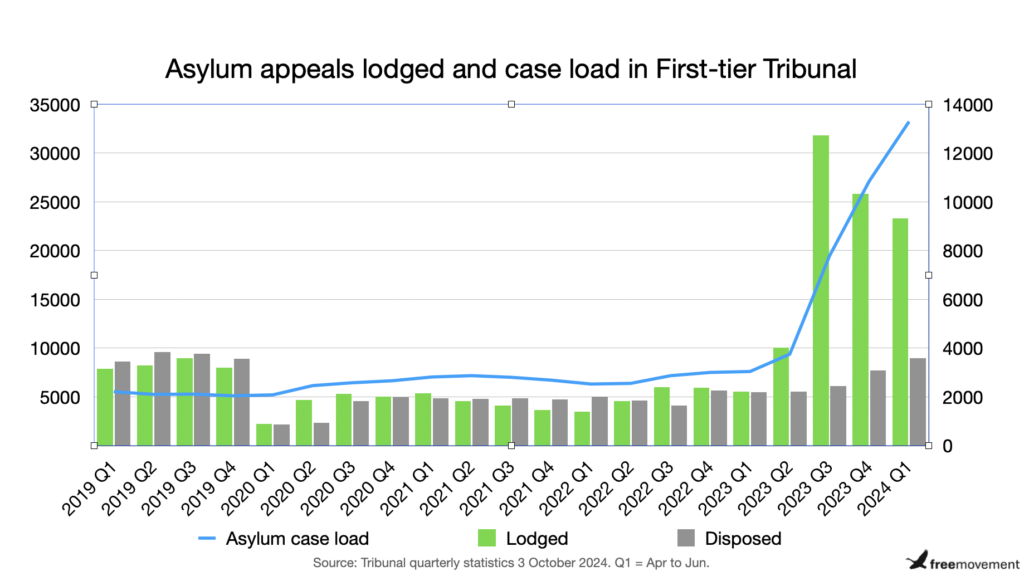

New figures published today show the asylum appeals backlog had risen to 33,227 cases at the end of June 2024, under the last government. In the period April to June 2024, the immigration tribunal received 9,318 asylum appeals and disposed of 3,598 asylum appeals.

These figures look bad as they are. But they actually hide the reality of what is going on in the asylum system because they are out of date and things are moving quickly at the moment. Numbers of appeals lodged has been decreasing since the end of 2024. Since June 2024, they will have been increasing again.

We need some context.

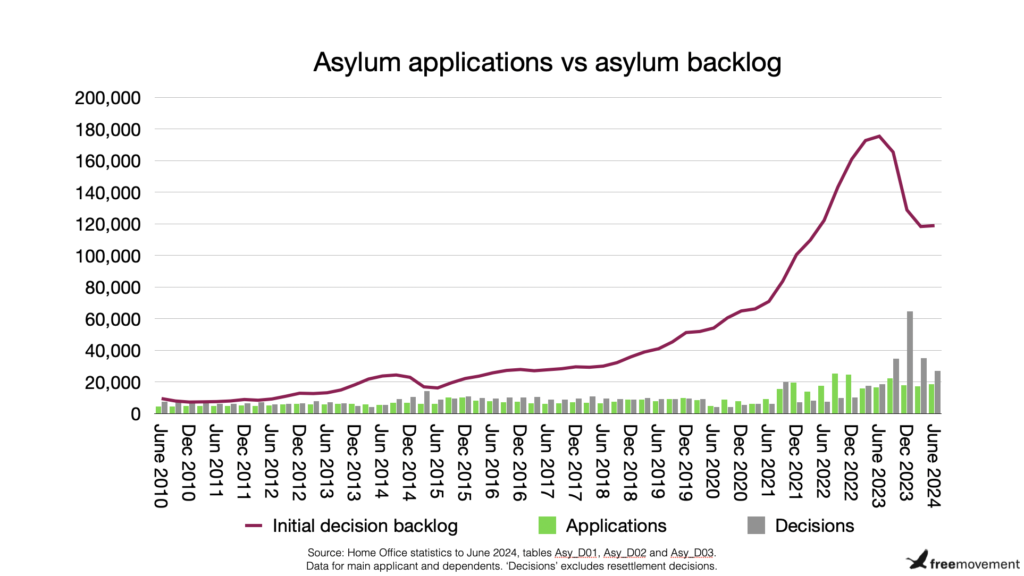

The following chart shows the initial decision backlog as well as asylum applications and asylum decisions. You can see that the backlog rose. Then fell. The started to increase again very slightly. Meanwhile, the number of asylum claims remained relatively stable. But the number of asylum decisions increased dramatically. Then fell again. What is going on?

Old backlog goes up then down: 2017 to 2023

Before Priti Patel took over as Home Secretary in 2017, the number of outstanding asylum claims had been fairly stable at around 20,000 to 30,000 cases. On her watch, the asylum backlog rose very considerably. Meanwhile, the number of asylum claims actually remained very stable. Small boat arrivals increased from 2018 onwards. Initially, though, this represented a change of route by asylum seekers rather than an overall increase in numbers.

When overall numbers did start to increase in late 2021, the backlog was already high and rising. The backlog eventually reached a peak of over 175,000 outstanding cases by June 2023. The backlog then very belatedly started to fall very rapidly.

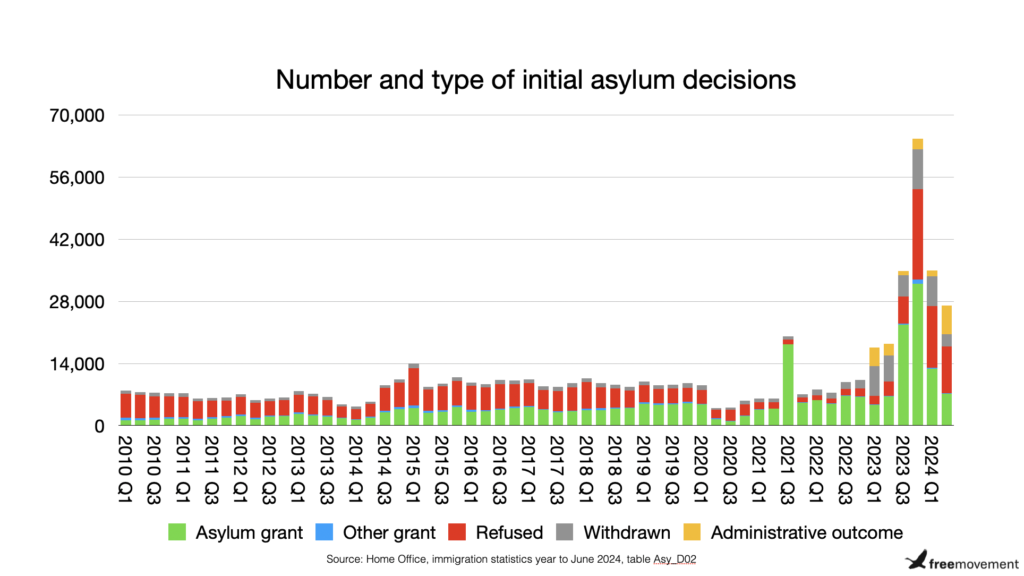

So, in the period running up to the end of 2023, the last government had been making considerable progress reducing the backlog it had allowed to build up. We can see from the previous chart that numbers of asylum claims remained stable. The reason the backlog fell was a rapid increase in the number of asylum decisions, as we can see in the following chart:

We can also see that the number of decisions rose rapidly but then also fell rapidly. I’ll come back to that fall in a moment.

In the period leading up to late 2023, the asylum grant rate was high at about 75% or so. This meant that the majority of asylum decisions were grants of asylum and there were relatively few refusals. It is only where a person is refused asylum that they might lodge an appeal.

In late 2023, though, because there was such a high volume of decisions, that meant numerically a lot more asylum refusals than normal and also therefore meant a lot more appeals being lodged than normal. That is why there is such a huge spike in appeals lodged in the period October to December 2023 (Q3 according to tribunal stats).

New backlog goes up: 2024

Let’s go back to the fall in the number of decisions from the start of 2024. We can see there was still a very substantial initial decision backlog. So why did the last government slow down decision making again? After all, the asylum backlog is hugely expensive because almost all those asylum seekers waiting for a decision have to be accommodated.

The answer is the Illegal Migration Act. The last government brought parts of it into force. This meant that anyone who had arrived on or after 7 March 2023 could not have their asylum claim processed.

This did not matter to begin with because there was already a huge backlog of asylum claims to work through for people who had arrived before then. But by the end of 2024 officials had run out of cases on which they could legally make decisions. So, asylum decision making slowed down again. The huge number of new caseworkers recruited to decide cases were left twiddling their thumbs.

Meanwhile, the backlog started to rise again. This is because asylum seekers continued to arrive. There was no increase in arrivals, just a steady flow.

What has happened since June 2024?

Soon after the new government won the general election on 4 July 2024, the bar on making asylum decisions was lifted. This means that asylum decision-making has resumed since then. We don’t yet have the figures on how many decisions of what kind have been made and we won’t get that until November.

We can make some guesses, though.

It seems reasonable to assume a similar number of decisions in the period June to August 2024 as at the peak of productivity in the period October to December 2023. As far as we know, the officials who were recruited for making asylum decisions were not sacked. So, there was a large number of trained officials ready to start making decisions if given the go-ahead. But there are unknowns. Some may have been reassigned. Staff turnover is very, very high in that part of the Home Office. The number of “administrative outcomes” (i.e. deemed asylum claim withdrawals) was far too high previously and it would have been sensible to stop that practice.

It seems likely that the grant rate will not have gone up since the last set of figures were released. It was hovering at around 60%. It had been high at least in part because claims from very high risk countries like Syria, Afghanistan and Eritrea had been prioritised and brought to the front of the queue. This means that there are fewer of those really strong asylum claims sitting in the backlog now.

So, the volume of decisions is very likely to have shot up since June 2024. And the proportion of refusals has probably remained either the same or gone up.

That means a high volume of asylum refusals. And that also means a high volume of asylum appeals.

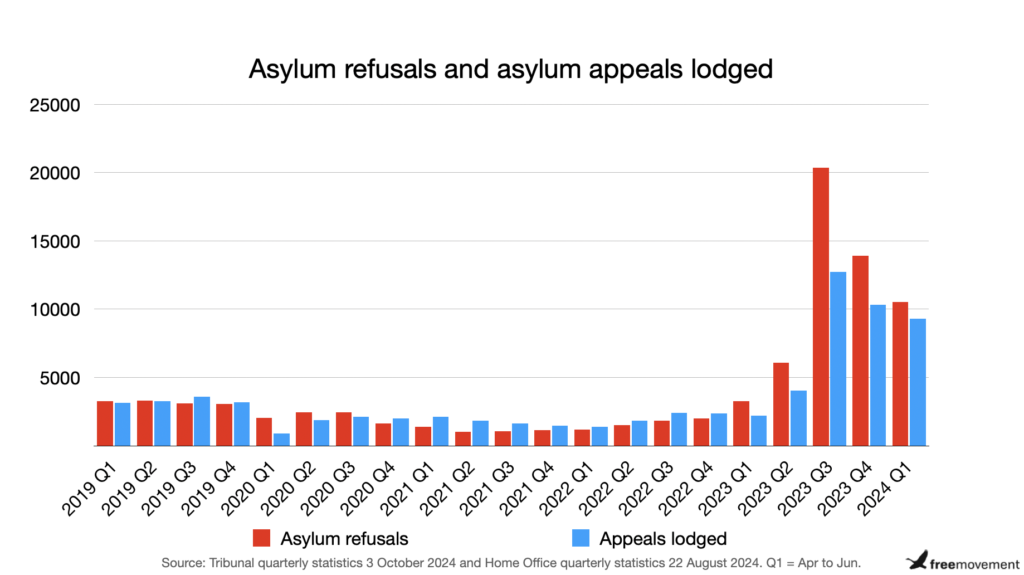

I’ve often wondered what percentage of refused asylum seekers lodge an appeal. I tried putting together a chart comparing asylum refusals and asylum claims lodged per quarter:

Weirdly, there are more appeals being lodged than refusals in some quarters, so I’m not sure I’ve got this right. Unhelpfully the Home Office and Ministry of Justice refer to different quarters, with the Home Office considering Q1 to be January to March and the MOJ considering Q1 to be April to June. But I think I adjusted for that. The deadline for lodging an asylum appeal is only 14 days, normally, so that delay shouldn’t make much difference. Anyway, the normal relationship is for there to be fewer appeals than refusals, although there is little consistency as to the percentage difference.

Anyway, we can see from the chart above and from the first chart in this blog post that there was a fall in the numbers of asylum appeals being lodged in the last three quarters which corresponds with the fall in the number of asylum refusals. That has not helped the tribunal much because the outstanding number of asylum appeals continued to rise because the tribunal can only process far fewer asylum appeals than it is receiving, even when those receipts were falling.

What will happen to the asylum appeals backlog?

We’ve just seen that asylum refusals are likely to have risen rapidly from June 2024. We might see something like 20,000 asylum refusals per quarter for several quarters in a row until the asylum backlog is cleared. Or, looking at it another way, the asylum backlog stood at around 120,000 cases. If around 40% are refused, that means about 48,000 asylum refusals over the period of time it takes to clear the backlog. If the rate of decision-making returns to that in late 2023, that will only take six months or so.

That’s a LOT of appeals incoming at a time when there is already a large backlog and the waiting time for appeals is already over a year on average.

It does not help that many of the people with pending appeals will not have legal representation, meaning that each appeal requires more judicial resource than if the person was represented. The number of asylum lawyers available has fallen in recent years and there is no way to rapidly increase our numbers. It was already the case that many asylum seekers could not find lawyers for appeals, and that was before the recent increase in appeals.

Unlike dealing with the initial decision backlog, there are no obvious or easy solutions here. But without some action and additional resources, it looks like the appeals backlog is going to rise rapidly and is going to stay high for a very long time. Asylum seekers are entitled to accommodation while awaiting the outcome of their appeals, which is going to make it hard for the new government to meet its pledge of ending the use of asylum hotels.