by Mihnea Cuibus & Peter William Walsh

A person who does not have the right to reside in the UK may be liable for removal – also known as return – from the UK. The government has pledged to increase the number of migrants being returned. This briefing note examines why returns declined during the 2010s, why they started to increase again after 2021, and what factors affect the numbers.

The number of people removed from the UK fell sharply in the 2010s, though it has partly recovered in recent years

The Labour government has pledged to remove more people with no legal right to be in the UK. To achieve this, it says that it has redeployed 1,000 staff to Immigration Enforcement. It also says it aims to increase detention spaces by around 15%, set up new support programmes in 11 countries to assist reintegration and negotiate new returns agreements with countries of origin. Labour also suggested a returns deal with the EU in the past, though it remains unclear how this would operate and whether an agreement will be reached.

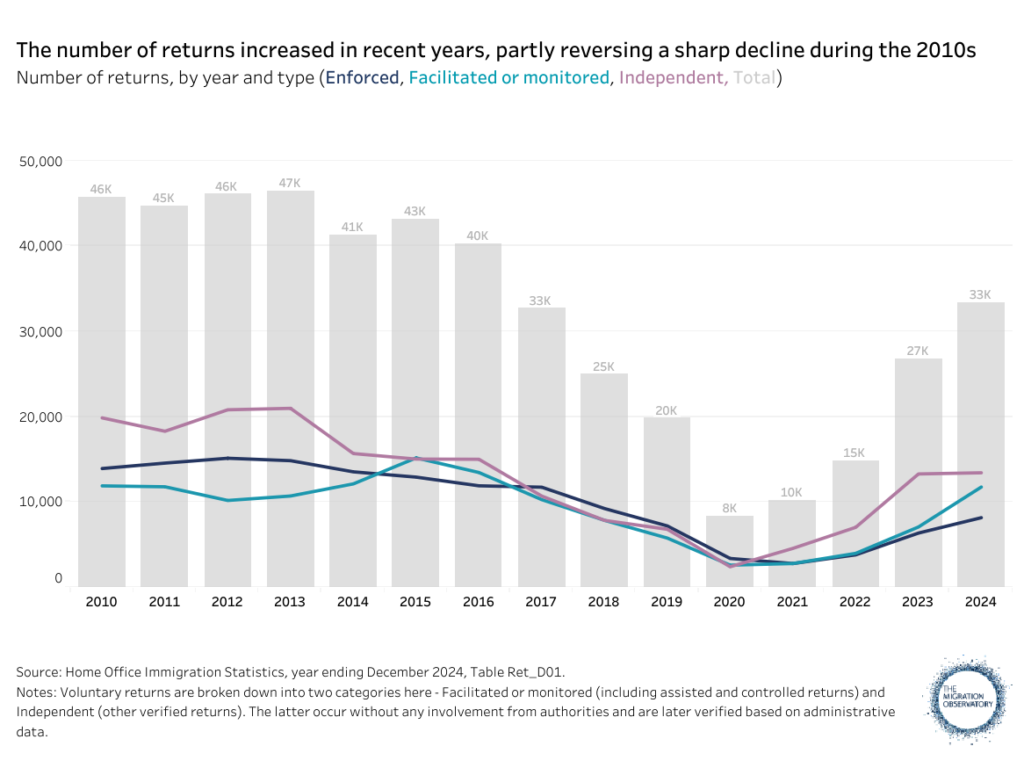

Total returns fell by 82% between 2013 and 2020, though numbers have partly recovered since. In 2024, around 33,400 people were returned to another country – higher than any year since 2016, though 28% lower than the 2013 peak.

These figures include three categories of returns – people who were forcibly removed from the UK (enforced returns), those who agreed to leave the UK voluntarily with some assistance or monitoring from the Home Office (facilitated or monitored returns), and those who left the UK voluntarily without contact with the authorities (which we term independent returns). The government generally prefers voluntary returns where they are feasible, in part because they are much cheaper.

All types of returns increased again from 2021 to 2024. Initially, the increase was driven by independent returns, which happen without any involvement from the authorities. It is unclear to what extent, if at all, government activity and policy affects the number of people returning independently (as opposed to other factors like economic conditions or the number of recent overstayers). From 2023 to 2024 (including under the Labour government elected in mid-2024), the largest increase was for voluntary returns monitored by the Home Office.

Figure 1

It is unclear how many people are living in the UK without permission and, thus, how the number of people returned compares to the total population liable for removal. The Home Office also does not provide any data on how many people it has identified or been in contact with who are liable for removal, such as people identified by immigration enforcement or refused visas in-country.

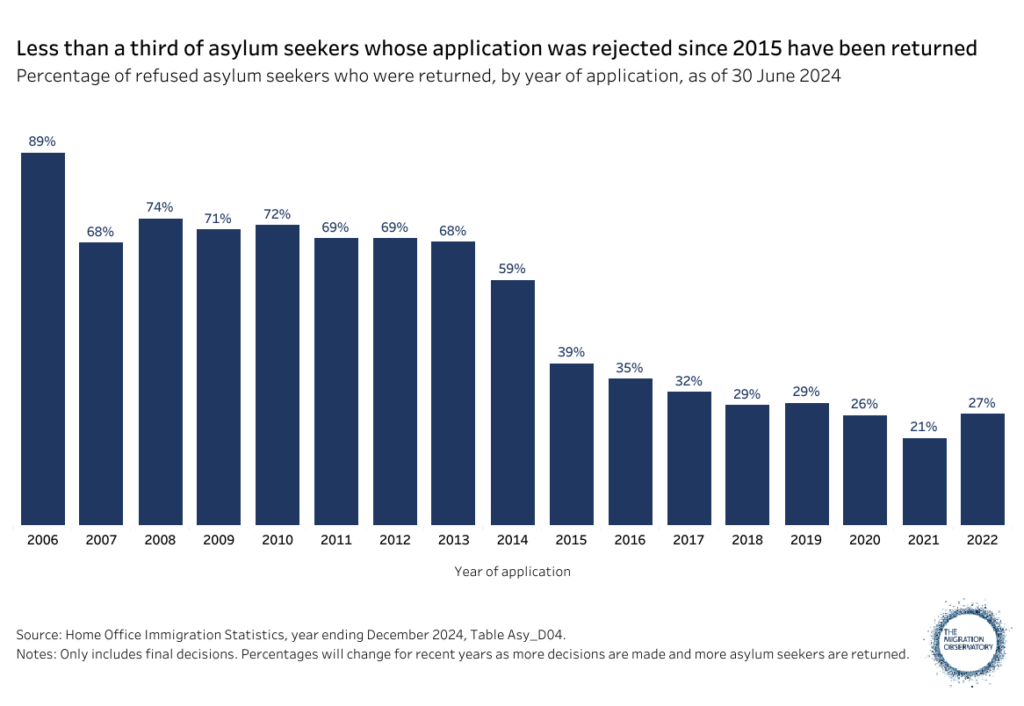

However, official figures do show the share of people who are removed within one subgroup of the unauthorised population – refused asylum seekers. Just under a third of people who applied for asylum between 2015 and 2022 and were refused protection had been returned by the end of June 2024. The percentage of refused asylum seekers who are returned has declined over time (though note that recent figures are subject to revision as more decisions are made and people are returned, which will affect recent cohorts most).

Figure 2

The sharpest decline took place between 2014 and 2015. One potential factor behind this change is the end of the “detained fast track” policy that had been used to expedite certain asylum seekers’ claims while they remained in detention. The policy ended in 2015 following a legal challenge, where the judge found that applicants did not have sufficient opportunity to put forward their asylum claim.

The decline in returns during the 2010s — and the increase since 2021 — have several potential explanations

It remains unclear exactly why returns declined so much during the 2010s before partially rebounding in the early 2020s. Several key factors have been put forward to explain these changes:

Legal Challenges

Legal challenges provide safeguards for individuals but also make it harder to remove people who do not ultimately qualify for relief. Statistics on legal challenges against being removed are limited but suggest their frequency has increased. A 2021 Home Office report found that at least one legal issue — most often an asylum claim — was raised in 73% of detentions in 2019, higher than two years before. Some of the challenges succeeded and led to a grant of asylum or other legal status, but the majority did not. Around 4-5% of asylum and human rights claims made by people detained ahead of removal in 2017-18 were successful.

Evidence also suggests that it now takes more attempts to complete a return procedure than in the past. A report from the National Audit Office found that the percentage of enforced return attempts that were cancelled increased from 11% in 2014 to 52% in 2019. Officials claimed that last-minute asylum claims and legal challenges “mostly explained” this increase.

Changes in referrals to Immigration Enforcement

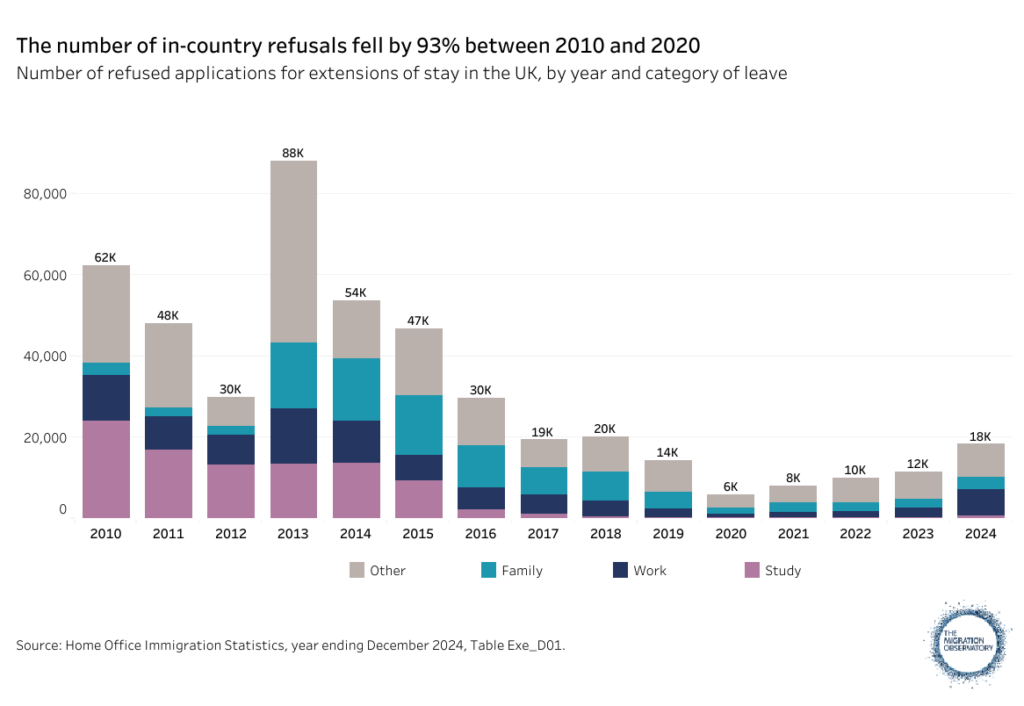

One factor influencing the number of returns is the number of people who are either referred to Immigration Enforcement or who come forward to leave voluntarily. One potential reason for the 2010s decline in returns is that, at least for some groups, fewer people eligible for removal were being referred. The Home Office does not publish data on the number of people it identifies as liable for removal. However, the number of people who applied for an extension of stay in the UK and were refused fell by 93% between 2013 and 2020, driven by a much lower refusal rate. People refused an extension become eligible for removal, so the decline may have meant there were fewer opportunities to conduct relatively straightforward returns involving people who have not necessarily lived in the UK for long periods. There were also higher numbers of human-rights related grants other than refugee status — people who might otherwise have been referred to Immigration Enforcement.

Figure 3

Similarly, the increase in returns after 2021 may have partly resulted from more relatively recent migrants becoming liable for removal, including being referred to Immigration Enforcement. On one hand, unauthorised migration to the UK appears to have increased following the emergence of the small boats route. On the other hand, authorised migration also increased sharply from 2022 to 2024. The number of visa overstayers will increase in periods with high migration, even if the percentage of people who overstay remains the same. Both trends will have led to more recent migrants becoming liable for removal. Recent migrants will be easier to remove than people who have lived in the UK for a long time and developed connections here. By contrast, people who have lived in the UK for long periods and may now have families and children here are both less willing to leave and more likely to qualify to remain on human rights grounds.

Costs and resources

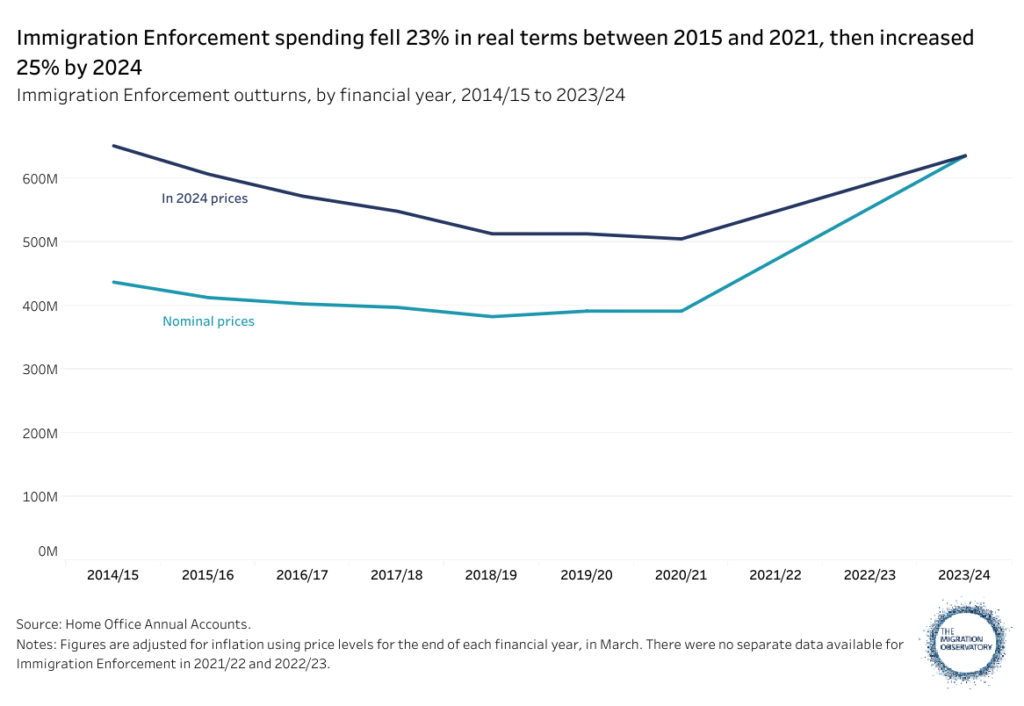

Fewer resources and increased costs may have been another reason for the decline in returns during the 2010s. Immigration Enforcement experienced significant budget cuts – funding fell by 23% in real terms between 2014/15 and 2020/21, according to Home Office accounts. Increased legal challenges added additional costs, including in cases where returns were not completed. In addition, enforced removals often require chartered flights and a large number of trained staff, which limits the number of people who can be removed from the UK within a given budget.

Conversely, higher resources are likely to have contributed to the increase in returns in recent years. Funding for Immigration Enforcement increased by 25% in real terms between 2020/21 and 2023/24, reversing most of the previous decline. The government further increased resources for Immigration Enforcement in the second half of 2024, redeploying 1,000 staff.

Figure 4

Administrative problems and delays

There is evidence that administrative factors play a role in returns, though their impact is hard to quantify. Slow processing of legal challenges made from detention can delay returns. An inspection report from 2015 found that delays in processing further submissions made by refused asylum seekers had been a significant barrier to removals. A UNHCR audit, which took a small sample of further submissions cases, suggested that it took the Home Office, on average, over 9 months to adjudicate them. Similarly, growing delays in asylum processing may also have contributed to the slowdown by making it harder to remove people whose asylum claims are refused. This is because they may develop stronger ties in the UK over time, including having children, that make them eligible to remain on human rights grounds.

Inefficient IT systems and management of casework operations can also hamper some return operations – as indicated by a 2023 report on the removal of foreign national offenders. Separately, some analysts attribute part of the decline in voluntary returns after 2015 to the decision to move operational responsibility for that service from a refugee charity to the Home Office itself. This may have reduced migrants’ awareness of and willingness to engage with the option of a facilitated return.

Cooperation with origin countries (or third countries)

The cooperation of origin country authorities is often necessary to enable returns – for example, to obtain the necessary documents before travel. A 2014-15 inspection report found that the most common reason for officials deciding not to detain someone who had been encountered by Immigration Enforcement and was liable for removal was that travel documents could not easily be obtained. It is difficult to measure whether and how other countries’ cooperation has changed over time since it is often not enshrined in agreements but results from informal collaborative relationships.

Although Brexit reduced the number of readmission agreements with origin countries, this does not seem to be a major cause of the decline in returns since the decline in returns long predates that change. The UK was also part of the Dublin Agreement before Brexit, which allowed it to return some asylum seekers who first passed through the EU back to those member states. However, leaving Dublin was not a significant driver of the decline in returns from the UK, as in practice, few people were returned under the agreement (an average of 560 a year between 2008-20).

It is difficult to evaluate how much each of these different factors has contributed to the trends in returns experienced by the UK in recent years. In summary, the decline in returns during the 2010s seems to have been the result of increased legal challenges, administrative delays, resource constraints, and fewer people being refused visa extensions in-country and thus being referred to Immigration Enforcement. The increase in returns from 2020 to 2024 may result from factors including a bounce-back from unusually low numbers of returns during the pandemic, budget increases, and higher immigration, both authorised and unauthorised. The latter will have increased the number of recently arrived migrants, including visa overstayers, who are easier to return.

Returns to most countries are lower than a decade ago

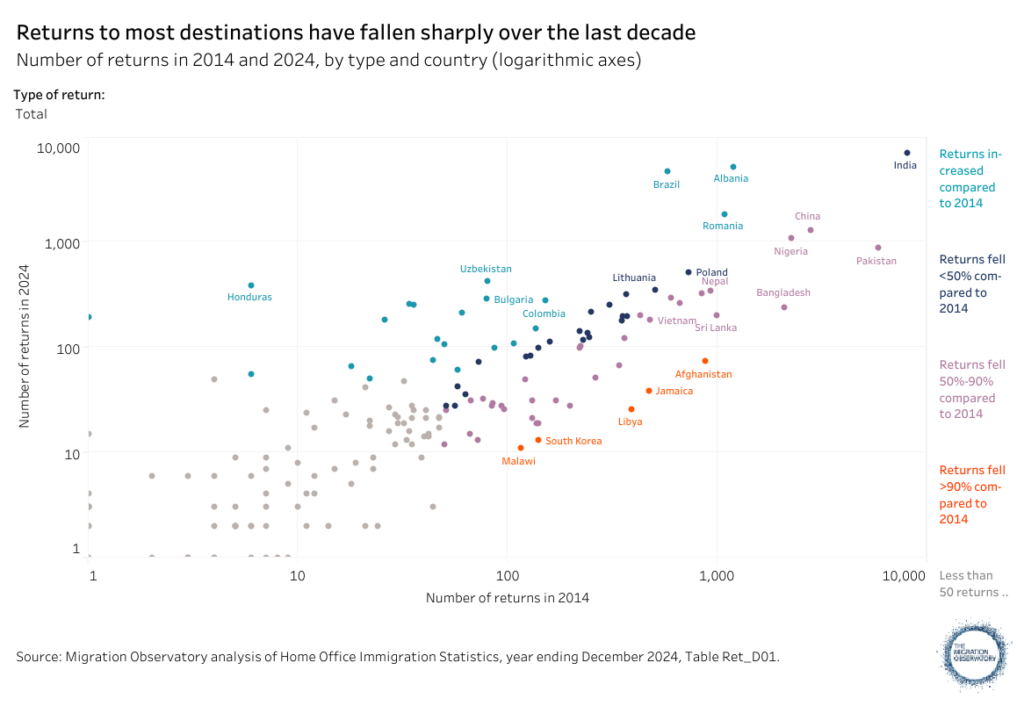

An important question about the decline is whether it has been driven by particular nationalities. Has the UK struggled to return people to several key countries, or has the decline been noticeable across the board? The evidence points to the latter. Returns to most countries, both enforced and voluntary, declined significantly between 2014 and 2024 (Figure 5).

This applies to some of the countries that the UK still returns the most people to, such as China (-53%), Nigeria (-51%), and Pakistan (-85%). Returns to seven countries of origin fell by more than 90%.

There are some exceptions, where returns either increased or held steadier between 2014 and 2024. These include India – the top destination for returns in both years – as well as Brazil, Albania, and several European and Central Asian countries. Diverging trends among different countries of nationality may result from changes in the make-up of the unauthorised population, as well as operational priorities for returns. For example, a sharp increase in Indian citizens returning independently of the government took place in the early 2020s. This might simply reflect people leaving the country over briefly overstaying a work or study visa. Similarly, large numbers of Albanians arrived in the UK on small boats in 2022, and returns increased sharply thereafter.

Figure 5

The share of recently refused asylum seekers returned from the UK varies greatly by country of origin

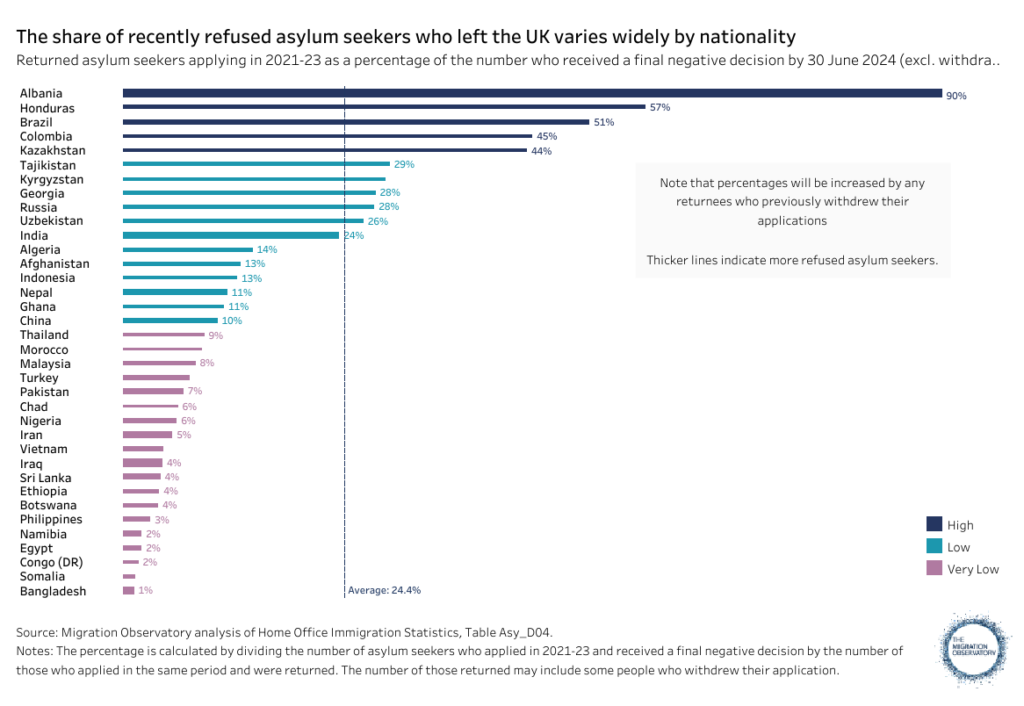

Since there are no reliable estimates of the number of people without a legal right to be in the UK, in this section, we examine a subset of this population – recently refused asylum seekers. In Figure 6, we look at people who applied for asylum between 2021 and 2023, comparing the number of those who received a final negative decision to the number of those who had been returned by 30 June 2024.

Across all nationalities, around a quarter of recently refused asylum seekers had been returned. However, the share varied widely by nationality. It was highest in the case of Albania, followed by Honduras and Brazil. However, some of the nationalities with the highest number of recently refused asylum seekers – such as Bangladesh, Iraq, or Iran – had return rates of well under 10%.

Figure 6

Based on these percentages, we divide countries into three main categories – High or Medium returns (>33%), Low returns (10-33%), and Very Low returns (<10%). Countries with fewer than 100 refused asylum seekers in 2021-23 are included in an ‘Other’ category.

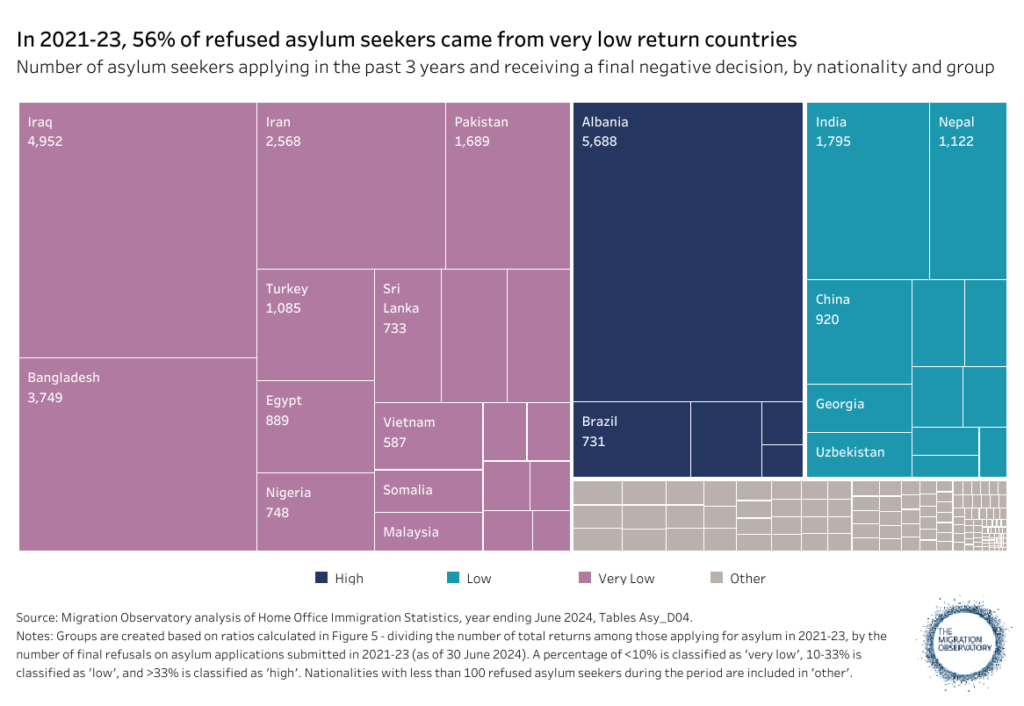

Among all those who applied for asylum between 2021 and 2023 and received a final negative decision by 30 June 2024, around 56% came from ‘very low return’ countries (Figure 7).

Figure 7

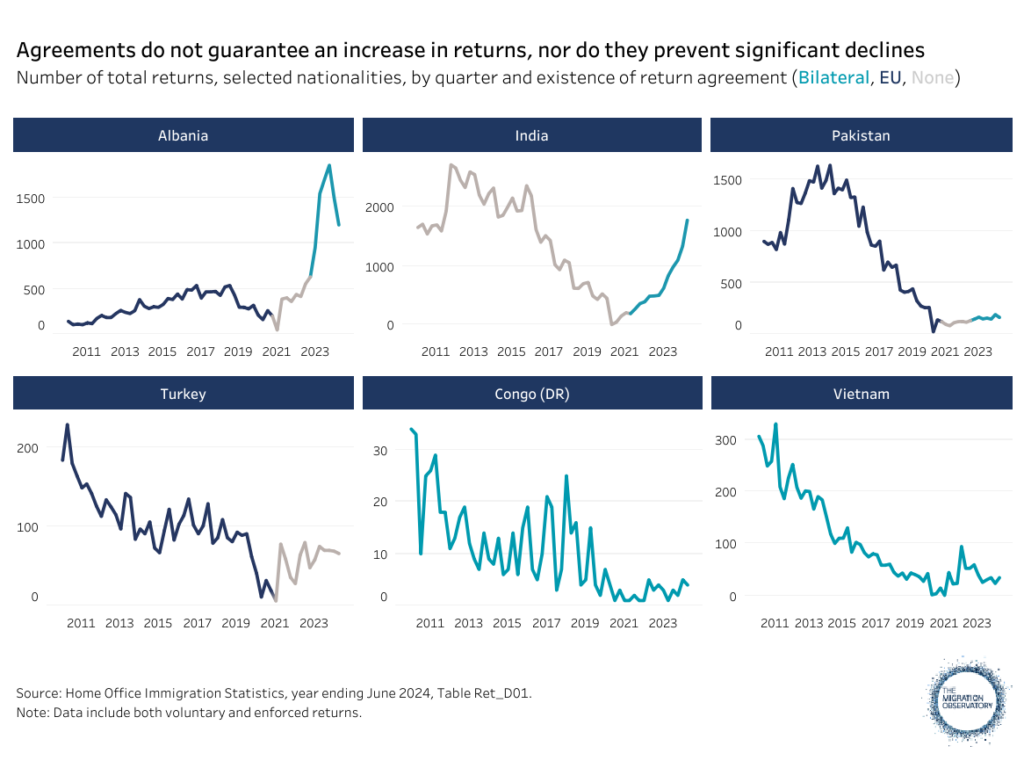

Returns agreements with countries of origin do not always lead to higher returns, though they may have an impact

A key part of both the previous and current government’s approach to returns has been negotiating return agreements with countries of origin. Such deals can streamline return procedures and logistics, make it easier to obtain travel documentation for those who need to be returned, organise reintegration processes, and incentivise origin countries through development aid and other policies.

However, a formal deal with an origin country does not guarantee effective cooperation in practice. For example, one study finds that EU readmission agreements had little to no effect on overall return rates. A study on Germany’s readmission agreements found that formal agreements often broke down at the implementation stage because origin countries had limited incentives to follow through and that informal links between lower-level officials could sometimes be more important than high-level diplomatic agreements. In some cases, poor diplomatic relations are likely to mean that neither formal nor informal cooperation are particularly likely.

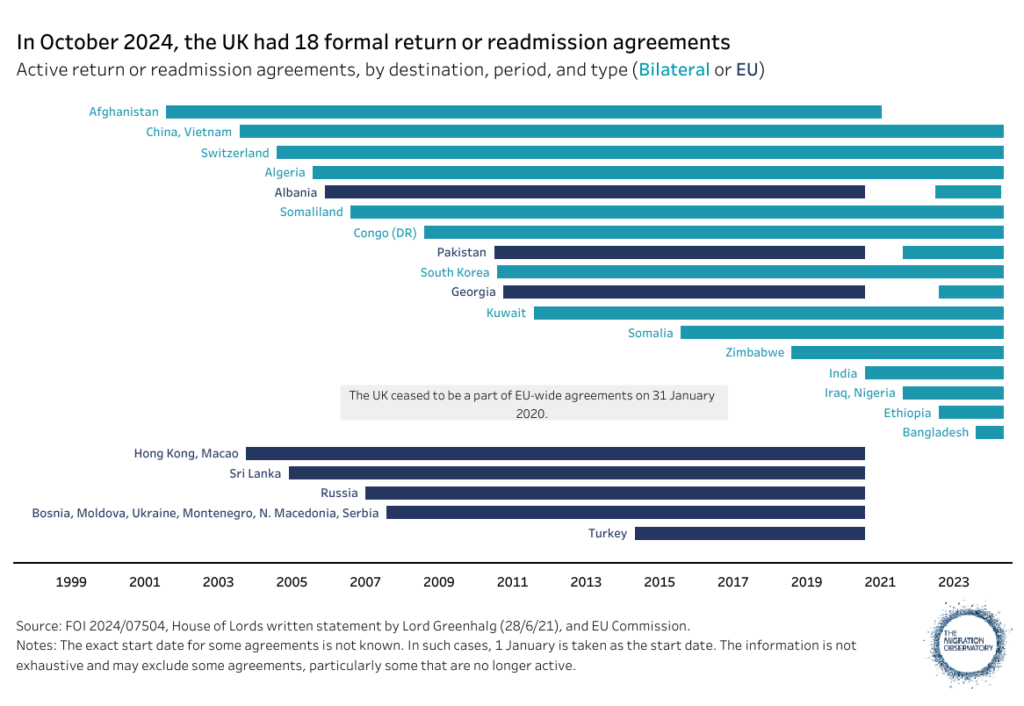

According to a freedom of information request, the UK had some kind of formal bilateral return agreement with 18 countries as of 1 October 2024. Half of these have been signed in the past five years (Figure 8). Before 2021, the UK was also covered by 14 of the EU’s 18 readmission agreements with third countries or territories. In three cases, the UK signed a new bilateral agreement to replace those that had been in place before it left the EU.

Figure 8

Formal agreements are neither necessary nor sufficient to ensure a high number of returns. The UK returns a significant number of people to countries it does not have a return agreement with, such as Brazil, Romania, or the Philippines. In 2023, around 54% of those returned were nationals of a country with which the UK had a formal returns agreement.

In some cases, such as Albania and India, returns rose sharply after an agreement was signed, though it remains unclear how much of this increase can be attributed to the respective deals (Figure 9). Many factors affect the number of returns to a specific country, including increases in unauthorised arrivals or a decision to prioritise removing a particular group, as was seen in the case of Albanians in 2022.

In other cases, by contrast, the UK returns very few people to countries it does have an agreement with, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo or Somalia. Some agreements, such as the one signed with Pakistan in August 2022, did not immediately lead to more returns. Returns to other countries, such as Vietnam, have declined sharply despite the existence of long-standing bilateral or EU-wide agreements (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Evidence gaps and limitations

There are many evidence and data gaps that make it difficult to get a full picture of deportations and returns. First, published statistics provide relatively little information on the circumstances under which people return other than whether they had previously claimed asylum. For example, anyone who overstays a visa and then leaves the country is included in returns statistics. However, some may have overstayed visas by only a few days or weeks. Their profile will be quite different from that of people who have been in the UK for months or even years, perhaps having also worked without permission. Similarly, there are no published statistics on returns by original visa or entry type (e.g., whether people entered without permission, or overstayed visit, work, study, or other visas).

A second major problem is the limited data on how many people are potentially subject to removal action. Using current statistics, it is hard to know whether the 2010s decline in returns (and the subsequent increase) results primarily from changes in the number of people being encountered by immigration enforcement, as opposed to a different share of those who were encountered by immigration enforcement (or otherwise known to the Home Office) leaving the country. This matters because it affects how we interpret the figures. For example, declining returns could, in theory, result from higher compliance (e.g. fewer people overstaying), or it could result from lower enforcement when non-compliance takes place. Without more data, it is difficult to know.

In response to freedom of information requests, the Home Office said it did not hold data on the cost of enforced vs voluntary returns; the number of those issued notices of liability to remove who were subsequently granted legal status (e.g. following a human rights claim); the number of foreign national offenders of different nationalities who had been removed vs not removed after finishing a prison sentence; and the number of people detained ahead of removal (as opposed to detained for initial processing). It declined to provide data on the number or nationalities of people arrested in immigration raids or updated figures on the number of legal challenges raised in detention and their outcomes on the basis that it intended to publish the figures in future.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Stephen Webb and Jonathan Thomas for comments on an earlier draft.