Small boats, big business

The industrialization of cross-channel migrant smuggling

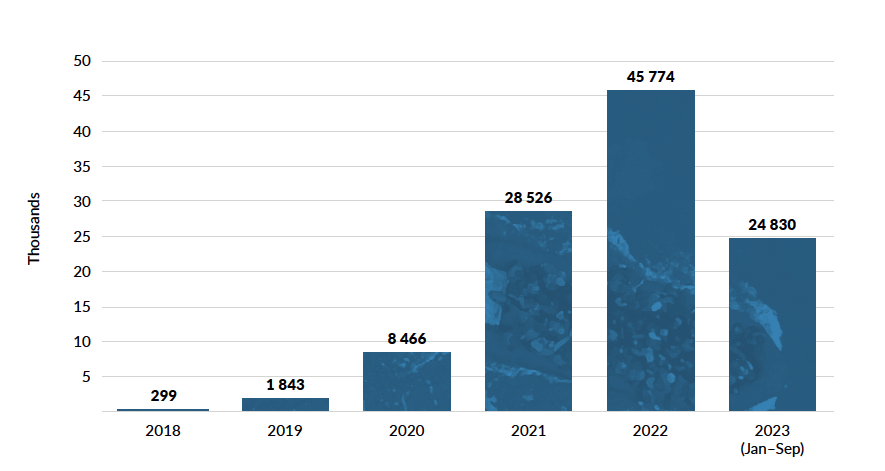

As of January 2024, over 100 000 people had crossed the English Channel using small boats since 2018. The current peak came in 2022, when over 45 000 people were detected arriving in the UK illegally using small boats launched from the coast of northern France. Although small in comparison with the flows of migrants risking the journey across the Mediterranean to reach Europe each year, this figure marked a record high for the UK since records began in 2018. The spike in the number of arrivals can be largely explained by the ‘industrialization’ of a system of smuggling migrants by boat, a process that began in 2018.

Crossing the English Channel by boat is a technique developed by human smugglers in response to tighter security in northern France adopted in an attempt to stem growing waves of migrants – the so-called ‘migrant crisis’ of 2015–2018. Smugglers had previously sought to hide their clients in trucks using the Channel Tunnel, but faced with heightened surveillance and interdiction by the authorities, began to shift towards small boats as a means of transport at once simple and efficient, yet far more perilous for the passengers. Brexit and the coronavirus pandemic are also factors behind this shift: the former raised fears among migrants that they would be subjected to tougher border controls, while both Brexit and the pandemic raised the price migrants had to pay for passage by truck (although this method has continued to be used).

These factors are not the only reason. Human smuggling networks have commercialized the small-boat route, keeping prices competitive and launching persuasive recruitment campaigns in migrants’ countries of origin. Operations have become more sophisticated and efficient. Smugglers manage the flow by temporarily holding migrants away from the coast, where law enforcement attention is concentrated. Once a boat or a flotilla has been dispatched, the next is prepared, reducing the time migrants spend in makeshift camps, and thus their likelihood of being apprehended. Law enforcement operations have driven innovation among smugglers, who have become adept at using small boats, from supply of the vessels to the point they are launched, and using departure points that are out of the spotlight of security agencies.

Iranian Kurdish criminal actors were the first to organize this method of crossing, but control over smuggling in the coastal region was quickly asserted by Iraqi Kurdish groups, who now are the arbiters of when migrants depart and from where. These groups have defined zones of interest, although violent competition over departure sites as well as pragmatic cooperation between clans are common. Albanian people smugglers – perceived in the British media as the most significant actor in this space – work under the auspices of Kurdish actors. During fieldwork for this study, Albanian migrants said that their Albanian smuggler reported to Iraqi Kurd networks, who made the decisions about departures.

Figure 1 Numbers of migrants detected using small-boat crossings, 2018 to September 2023. SOURCE: UK Home Office, Irregular migration detailed datasets and summary tables.

According to one smuggler based in Germany, a smuggling network tends to consists of between eight and twelve people. The kingpin usually lives in another country, together with a trusted person who controls the network for the kingpin. (Some smugglers continue to operate their networks from inside prison, often having smuggled in a mobile phone.) On the French coast, the other network members are assigned functions: three or four guide the migrants to the entry point; another three to four take care of logistics, involving transporting the boat engines, hulls and fuel to the launching point. The rest work as guards, monitoring the area for rival networks and law enforcement agents. It is a highly lucrative business, with one source estimating that smuggling networks can earn more than a million US dollars (approximately €920 000) a month. Xavier Delrieu, head of the French Office for the Fight against the Illicit Trafficking of Migrants, estimated that the value of the migrant smuggling industry in 2022 was €150 million.

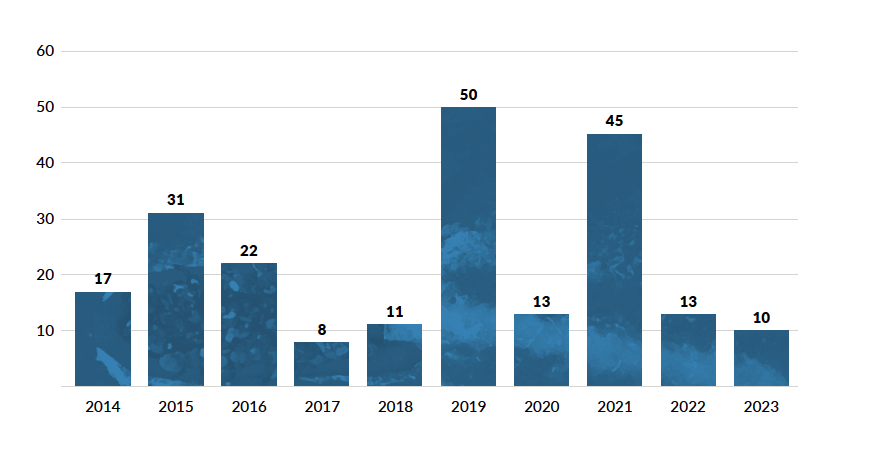

The migrant bears the overwhelming burden of risk – physical, psychological and legal. The boats are often overloaded with passengers to maximize profits, and structurally unsuited for such dangerous seas and capsize. Some make the journey successfully; others are intercepted, but many drown at sea. According to the IOM Missing Migrants project, between 2014 and September 2023, 220 migrants and refugees went missing or died, including children, when attempting to cross the Channel. The greatest proportion of deaths – almost 60% – have occurred since 2019 (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 Migrant deaths in the English Channel, by year. SOURCE: IOM, Missing Migrants

This report explores how the English Channel has become a commercialized human smuggling route. It analyzes the shift in the mode of human smuggling transportation from land to sea, from trucks using the Channel Tunnel to rigid inflatable boats (RIBs). It explores how the smuggler networks manage payments for migrants, enforce control at the coastal areas and secure the supply of vessels. It also provides an anatomy of a typical crossing on this route, highlighting the complex nature of migrants’ journeys, and provides recommendations for how to delink the steady demand among migrants to reach the UK from the criminal smuggling networks that organize the crossings.

The report draws from triangulated fieldwork that engaged with people working in the smuggling trade; this was conducted in the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Afghanistan, Iraq and Albania in 2022 and 2023. It also uses material from interviews with migrants and researchers who have experienced the crossing, reviews of court proceedings, as well as a literature review.